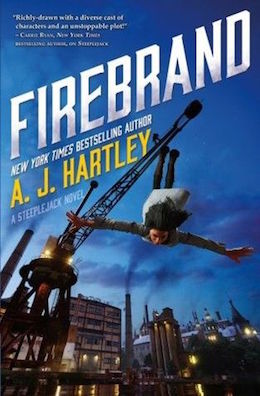

Anglet Sutonga’s work as a steeplejack atop the towering roofs of Bar-Selehm may have primed her resume for her new job as a spy, but it certainly didn’t prepare her for it. Last year’s South African-inspired Steeplejack saw Ang flying from rooftops with enough poise and grace that she could (and did) keep a baby strapped to her back all the while. This summer, A.J. Hartley has released a sequel that pushes Ang far from her comfort zone of smoking precipices and constant danger. In Firebrand, our protagonist enters the world of the political elite—a world that is wealthier and more perilous than she could have imagined.

Bar-Selehm’s political turmoil isn’t new. Colonized by the white Feldish, its native Mahweni population is forced into constant poverty and displacement. Ang’s own people, the Lani—brought from afar to work and mine the land—don’t fair much better. Add to this the threat of the outside Grappoli army, and it is unsurprising (and dreadfully familiar) that Bar-Selehm’s powerful can’t agree on how best to protect its people—or even exactly who its people are. When designs for a terrifying new weapon are stolen by an unknown force, Ang’s employer, Josiah Willinghouse, sees an opportunity to topple his racist, warmongering parliamentary opponents. All Ang can see, as she confronts harrowing fights and drawing room gossip, are the faces of the people she’s trying to save.

Mahweni refugees pour into Bar-Selehm daily, uprooted from their homes by Grappoli attacks. Ang is distressed when she witnesses these displaced families, and not just because she can relate to their placelessness and oppression. She has also been to parliament and heard first-hand the new Heritage party’s plans to segregate and crack down on the city’s black and brown populations. And so she’ll do anything to untangle the messy threads of allyship, petty grievance, and extramarital affairs. If the stakes in Steeplejack were personal, the ones in Firebrand are political—which is to say, also personal.

Firebrand follows Ang as she attempts to connect the dots between three political parties, a foreign army, a dead thief, and a live one. A familiar cast of characters joins her in this puzzle, (including my two favorites from the previous novel: the genius reporter Sureyna, and the catty and longsuffering Dahria Willinghouse). New to Ang’s mismatched group of friends, however, is Madame Nahreem, the Willinghouses’ grandmother. Madame Nahreem is in many respects the heart of the novel, both in terms of character development and in pinpointing the intricacies of race and identity that form Firebrand’s theme. When Ang is tasked with masquerading as a foreign princess to infiltrate the exclusive Elitius Club, it is Madame Nahreem that trains her. “To be a lady,” she tells Ang, “you must unlearn seventeen years of thinking yourself an underling.” She, after all, was a Lani woman from the slums, just like Ang, until she married into a prestigious white family—if anyone knows how to erase and create a new identity, it’s her. The relationship she forms with Ang as a result of this mutual identity mapping is a fascinating one, not quite maternal, but not merely one of mentor and student, either. They are alike in values and social injustice, and Firebrand states quite clearly that these run far thicker than blood or water.

Despite loving the diversity and themes of Firebrand, it did feel very much like the second in a series to me. A great deal happened, but the pacing was stilted; at times, it felt as if Ang were collecting relevant plot points rather than experiencing life (a result, perhaps, of a plot too finely-stitched). The final stretch of the book, especially, introduced a number of new plot points and characters that will obviously be vital to future novels, but which were awkward and forced in the context of Firebrand itself. I am, that said, not dissuaded from reading those sequels. If Firebrand was disappointingly expository, I have faith that said exposition will crescendo in its successors, which are bound to be filled to the brim with bigger action and bigger ideas.

Books like those in Hartley’s Steeplejack series would be important at any time in history, but particularly at this juncture. Politically savvy and emotionally potent, they are still fun enough to trick their readers into thinking otherwise.

Firebrand is available now from Tor Teen.

Read an excerpt from the novel here on Tor.com

Emily Nordling is a library assistant and perpetual student in Chicago, IL.